Referral 1

Funding opportunities in South Africa

Agro-processing Support Scheme

Export Marketing And Investment Assistance

National Youth Development Agency

Seda Technology Programme

Seed Fund

Agriculture

Aquaculture Development And Enhancement Programme (Adep)

Black Industrialist Scheme

Capital projects feasibility Programme

Clothing and textile Competitiveness Improvement Programme

Government funding

Industrial Development Corporation of SA

Industry Innovation Support

International aid and donor funding

Isibaya Fund

KZN Growth Fund

National Empowerment Fund

Sector Specific Assistance Scheme

Small Enterprise Finance Agency

South African Micro-finance Apex Fund

Strategic partnership Programme

Technology And Human Development Programme (Thrip)

Technology Innovation Agency

Source: Funding Opportunities

Referral 2

A Father’s Impact on Child Development

Children with active, involved fathers during childhood and adolescence experience significant advantages. The Fatherhood Project has researched the impacts of father engagement during childhood development stages. Both The Fatherhood Project and our Father Engagement Program are dedicated to improving children’s and families’ health and well-being by empowering fathers to be knowledgeable, active, and emotionally engaged.

Here Are 10 Important Facts From Their Research:

10 Facts About Father Engagement

- Attachment: Fathers and infants can be as attached as mothers and infants. When both parents are involved, infants form attachments to both from birth.

- Health Outcomes: Father involvement is linked to positive child health outcomes in babies, like improved weight gain in preterm infants and higher breastfeeding rates.

- Authoritative Parenting: Father involvement using authoritative parenting (loving with clear boundaries and expectations) leads to better emotional, academic, social, and behavioral outcomes for children.

- Future Success: Children close to their father are twice as likely to enter college or find stable employment after high school, 75% less likely to have a teen birth, 80% less likely to go to jail, and half as likely to experience multiple depression symptoms.

- Critical Role: Fathers are crucial in child development. Father’s absence hinders development from infancy to adulthood, with psychological harm persisting throughout life.

- Quality Over Quantity: The quality of the father-child relationship matters more than the hours spent together. Non-resident fathers can positively affect children’s social and emotional well-being, academic achievement, and behavioral adjustment.

- Sociability and Self-Control: High levels of father involvement correlate with higher levels of sociability, confidence, and self-control in children. They are less likely to act out in school or engage in risky behaviors in adolescence.

- Academic Achievement: Children with actively involved fathers are 43% more likely to earn A’s and 33% less likely to repeat a grade than those without engaged dads.

- Behavioral and Economic Benefits: Father engagement reduces behavioral problems in boys and decreases delinquency and economic disadvantage in low-income families.

- Psychological Benefits: Father engagement reduces psychological problems and depression rates in young women.

The impact of fathers and father figures is substantial. While father involvement has many positive aspects, the effects of their absence can be detrimental.

Father Absence

According to the 2007 UNICEF report on child well-being in advanced nations, kids in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. rank extremely low in social and emotional well-being. A largely ignored factor among child and family policymakers is the prevalence and devastating effects of father’s absence in children’s lives.

Studies show that children without fathers at home suffer greatly. Even before birth, a father’s attitudes regarding the pregnancy, prenatal behaviors, and the father-mother relationship may indirectly influence risk for adverse birth outcomes. School-aged children with good relationships with their fathers are less likely to experience depression, disruptive behavior, or lying and more likely to exhibit prosocial behavior.

Fatherless homes significantly impact adolescents. These children are more likely to experience the effects of poverty. Former President George W. Bush stated, “Over the past four decades, fatherlessness has emerged as one of our greatest social problems. We know that children who grow up with absent fathers can suffer lasting damage. They are more likely to end up in poverty or drop out of school, become addicted to drugs, have a child out of wedlock, or end up in prison. Fatherlessness is not the only cause of these things, but our nation must recognize it is an important factor.”

Many individuals recognize the lasting impact of a father’s presence in a child’s life. Many admit to struggling with feelings of abandonment and low self-esteem due to a lack of a father’s love. Some have turned to drugs, alcohol, risky sexual activities, unhealthy relationships, or other destructive behaviors to numb the pains of fatherlessness.

The absence of their father is not an isolated risk factor, but it can affect children’s development. It’s important to consider, as many would argue, that one parental role is more significant than the other. That is not true.

According to Psychology Today, researchers have found these narratives to be true. The effects of a father’s absence on children are incredibly negative:

- Diminished Self-Concept and Security: When fathers are uninvolved, children report feeling abandoned, struggling with their emotions, and experiencing self-loathing.

- Behavioral Problems: Fatherless children have more difficulties with social adjustment, are more likely to report problems with friendships, and manifest behavior problems. Many develop a swaggering, intimidating persona to hide underlying fears, resentments, anxieties, and unhappiness.

- Poor Academic Performance: Fatherless children struggle academically, scoring poorly on reading, mathematics, and thinking skills tests. They are more likely to skip school, be excluded, leave early, and less likely to attain academic and professional qualifications in adulthood.

- Delinquency and Youth Crime: 85% of imprisoned youth have an absent father. Fatherless children are more likely to offend and go to jail as adults.

- Promiscuity and Teen Pregnancy: Fatherless children are more likely to experience problems with sexual health issues, including a greater likelihood of having intercourse before the age of 16, foregoing contraception during first intercourse, becoming teenage parents, and contracting sexually transmitted infections. Girls manifest an object hunger for male attention and, feeling the emotional absence of their fathers as a personal rejection, become vulnerable to exploitation by adult men.

- Drug and Alcohol Abuse: Fatherless children are more likely to smoke, drink, and abuse drugs in childhood and adulthood.

- Homelessness: 90% of runaway children have an absent father.

- Exploitation and Abuse: Fatherless children are at greater risk of suffering physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. They’re five times more likely to experience physical abuse and emotional maltreatment, with a 100 times higher risk of fatal abuse. Preschoolers not living with both biological parents are 40 times more likely to be sexually abused.

- Physical Health Problems: Fatherless children report significantly more psychosomatic health symptoms and illnesses like acute and chronic pain, asthma, headaches, and stomach aches.

- Mental Health Disorders: Children without fathers are consistently overrepresented in a wide range of mental health problems, especially anxiety, depression, and suicide.

- Life Chances: As adults, fatherless children are more likely to face unemployment, low incomes, remain on social assistance, and experience homelessness.

- Future Relationships: Children who grow up without a father tend to enter partnerships earlier, are more likely to divorce or dissolve their cohabiting unions, and are more likely to have children outside marriage or partnerships.

- Mortality: Fatherless children are more likely to die as children and live four years less on average.

Tips for Dads

Dads! It’s vital to be actively involved in your child’s life – whether you live together or not. Here are great ways to create healthy, positive engagement with your children (adapted from the Modern Dad Dilemma):

- Speak Positively to and About Their Mother: It is essential to be on the same page as their mother about your role. Be clear and respectful, emphasizing your desire to be an involved father. Speak positively about her in front of your children to show respect and maintain a healthy relationship.

- Create a Vision for Fatherhood Engagement: Think about what you hope your children will say about you as a father in the future. This will help you clarify your purpose and guide your decisions.

- Be the Bridge Between Your Father and Your Children: Reflect on your relationship with your father and decide what positive aspects to pass on to your children and what negative aspects to avoid.

- Establish Ritual Dad Time: Spend regular one-on-one time with your children doing activities you both enjoy. Make sure to talk and build a strong connection.

- Know Your Children: Be interested in their lives, know their friends, and understand their stressors. Show they’re worthy of your time and attention.

- Be Known by Your Children: Share stories about your childhood and experiences to humanize yourself and initiate meaningful dialogue.

All For Kids hopes you recognize your tremendous value as Fathers. You can make a lasting difference in your children’s lives, and we appreciate you more than you know!

Source: Allforkids.org – a-fathers-impact-on-child-development

Referral 3

Courts in South Africa

Constitutional Court

The Constitutional Court was established in 1996 by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. The court is situated at Constitutional Hill Precinct in Braamfontein, Johannesburg. There are 11 judges of the Constitutional Court, namely a Chief Justice, Deputy Chief Justice and 9 Judges. A matter must be heard by at least 8 judges.

The Constitutional Court is the apex court in South Africa. Its decisions cannot be changed by any other court. The court decides constitutional and general matters. A constitutional matter includes any issue involving the interpretation, protection or enforcement of the Constitution. General matters are heard if the Constitutional Court grants leave to appeal. A general matter is one that is of general and public importance.

The Constitutional Court makes the final decision whether a matter is within its jurisdiction.

Only the Constitutional Court hears –

(a) Disputes between organs of state in the national or provincial sphere concerning the constitutional status, powers or functions of any of those organs of state;

(b) The constitutionality of any parliamentary or provincial Bill;

(c) The constitutionality of any amendment to the Constitution;

(d) A matter that Parliament or the President has failed to fulfil a constitutional obligation;

(e) A matter to certify a provincial constitution in terms of section 144 of the Constitution.

A matter may be brought directly to the Constitutional Court or appealed directly to the Constitutional Court from any other court. Leave of the Constitutional Court is required to do so.

Website: www.constitutionalcourt.org.za

Supreme Court of Appeal

The Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) is based in Bloemfontein in the Free State. It was established in 1910 as the Appellate Division. It is designated as the Supreme Court of Appeal by the Constitution. The court consists of a President, a Deputy President and a number of judges of appeal.

Ordinarily, proceedings are presided over by three or five judges, depending on the nature of the appeal. An appeal in a criminal or civil matter may be heard before a court consisting of three judges. A court consisting of a larger number of judges hear a matter of importance.

The SCA decides appeals except in labour and competition matters. Appeals to the SCA emanate from the High Court of South Africa or a court of a similar status to the High Court. Except for the Constitutional Court, no other court can change a decision of the SCA. The SCA may change its own decision.

The final decision of the SCA is the one supported by most of the judges listening to the case. If a judgement is not agreed to by a majority of the judges, the matter is adjourned and recommenced afresh before a new court. The President of the SCA determines the constitution of the new court.

Website: www.supremecourtofappeal.org.za

High Courts

The High Court of South Africa consists of the following Divisions:

(a) Eastern Cape Division, with its main seat in Grahamstown.

(b) Free State Division, with its main seat in Bloemfontein.

(c) Gauteng Division, with its main seat in Pretoria.

(d) KwaZulu-Natal Division, with its main seat in Pietermaritzburg.

(e) Limpopo Division, with its main seat in Polokwane.

(f) Mpumalanga Division, with its main seat in Mbombela.

(g) Northern Cape Division, with its main seat in Kimberley.

(h) North West Division, with its main seat in Mahikeng.

(i) Western Cape Division, with its main seat in Cape Town.

Each Division of the High Court consists of a Judge President, one or more Deputy Judges President and judges. The number of judges in each Division are determined in accordance with prescribed criteria and approved by the President.

Each Division has an area of jurisdiction which comprises of any part of one or more provinces. Each Division has a main seat and one or more local seats. A local seat has its own (exclusive) area of jurisdiction. Appeals arising from a decision of a single judge or of a Magistrate’s Court within the local seat, may, by direction of the Judge President be heard at the main seat of the Division. The main seat has concurrent (the same) appeal jurisdiction over a local seat. Judges are assigned within the Division by the Judge President. The High Court may sit elsewhere than the main or local seat to hear a matter, as determined by the Judge President after consulting the Minister. The reasons for doing so are expediency or the interests of justice.

A civil matter heard by a court of first instance, meaning that the matter is not an appeal matter, is presided over by a single judge. Any matter may be heard by a court consisting of not more than three judges. A single judge hearing a civil matter may discontinue the hearing and refer it for hearing to the full court of that Division. This is done inconsultation with the Judge President or, in the absence of both the Judge President and the Deputy Judge President, the senior available judge.

The law relating to criminal procedure determines the number of judges hearing a criminal case as a court of first instance.

Two judges hear any civil or criminal appeal. If the judges hearing the appeal do not agree, then at any time before a judgment is handed down, a third judge will be added to hear the appeal. The decision of the majority of the judges of a full court of a Division is the decision of the court. Where the majority of the judges disagree, the hearing is adjourned and commenced from the start (de novo) before a court consisting of three other judges.

The High Court decides constitutional matters, with two exceptions. The Constitutional Court may agree to hear the matter directly or an Act of Parliament may assign another court of a status similar to the High Court to hear the constitutional matter. The High Court decides other matters that have not been assigned to another court by an Act of Parliament.

The jurisdiction of the High Court to hear any matter includes –

(a) All persons residing or being in the Division;

(b) All causes arising and all offences triable within its area of jurisdiction;

(c) All other matters which it may legally recognise;

(d) Appeals from all Magistrates’ Courts within the area of the Division; and

(e) Review of the proceedings of Magistrates’ Courts.

Local and Main Seats of the Divisions of the High Court

| DIVISION | COURT AND ITS MAIN SEAT | COURT AND ITS LOCAL SEAT(S) |

| Eastern Cape | Eastern Cape High Court, Grahamstown | Eastern Cape High Court, Bhisho |

| Eastern Cape High Court, Mthatha | ||

| Eastern Cape High Court, Port Elizabeth (Gqeberha) | ||

| Free State Division | Free State High Court, Bloemfontein | |

| Gauteng Division | North Gauteng High Court, Pretoria | South Gauteng High Court, Johannesburg |

| KwaZulu-Natal Division | KwaZulu-Natal High Court, Pietermaritzburg | KwaZulu-Natal High Court, Durban |

| Limpopo Division | Limpopo High Court, Polokwane | Limpopo High Court, Lephalale |

| Limpopo High Court, Thohoyandou | ||

| Mpumalanga Division | Mpumalanga High Court, Mbombela | Mpumalanga High Court, Middelburg |

| Northern Cape Division | Northern Cape High Court, Kimberley | |

| North West Division | North West High Court, Mahikeng | |

| Western Cape Division | Western Cape High Court, Cape Town |

The area of jurisdiction of each of these courts is the area of jurisdiction or part of the area of jurisdiction, as the case may be, of the Division in question.

Website: https://www.judiciary.org.za/index.php

Circuit Courts of the Divisions of the High Court

Circuit courts are part of the High Court. Circuit courts serve far flung and rural areas. Circuit courts are established by the Judge President of a Division by way of a notice in the Gazette. A Circuit court’s jurisdiction applies within the area of the Division. The area of jurisdiction of a Circuit court is the circuit district. Circuit courts adjudicate civil or criminal matters. The boundaries of a circuit district may be altered by notice in the Gazette. Circuit courts are held at least twice a year. The court is presided over by a judge of the Division. The judge president of the division determines the times and places for the sittings of the court to hear the matters.

Website: https://www.judiciary.org.za/index.php

Important officers in a High Court Division:

The Registrar of the High Court – The functions of a registrar are mainly administrative. The registrar also has semi-judicial duties, e.g. issuing civil process (summonses, warrants, subpoenas) and so on. Other important duties of the registrar are that of taxing-master for that particular High Court division. Registrars also compile case lists, arrange available courts, lend assistance to judges in general and keep records.

The Family Advocate– The Family Advocate assists the parties to reach an agreement on disputed issues, namely custody, access and guardianship of children. If the parties are unable to reach an agreement, the Family Advocate evaluates the parties’ circumstances in light of the best interests of the child and makes a recommendation to the Court with regard to custody, access or guardianship.

The Master of the High Court– The Master’s Branch is there to serve the public in respect of:

- Deceased Estates;

- Liquidations (Insolvent Estates);

- Registration of Trusts;

- Tutors and Curators; and

- Administration of the Guardian’s Fund (minors and mentally challenged persons).

The Sheriff of the court – The Sheriff is an impartial and independent official of the Court appointed by the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development who must serve or execute all documents issued by our courts. These include summonses, notices, warrants and court orders.

The Directors of Public Prosecutions – are responsible for all the criminal cases in their provinces, so all the prosecutors are under their control. The police bring information about a criminal case to the Director of Public Prosecutions or his/her representative prosecutors. The Director of Public Prosecutions or his/her representative prosecutor then decides whether there is a good reason to have a trial and whether there is enough information to prove in court that the person is guilty.

The State Attorney – The State Attorney’s Division of the Department of Justice functions like an ordinary firm of attorneys, except that its clients are the different departments of government and not private individuals. The state attorney’s major function is to protect the interests of the State by acting for all government departments and administrations in civil cases, and for officials sued in their official capacity.

Tax Courts

Tax Courts are established by the President of the Republic by proclamation in the Gazette. In March 2003 the tax courts were established for areas. The special income tax courts constituted before 1 April 2003 for the hearing of income tax appeals were abolished. A tax court is established for the area of the Division of the High Court.

| Division of the High Court of South Africa | Seats of tax courts |

| Western Cape Division | Cape Town |

| Eastern Cape Division | Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth (Gqeberha) |

| Northern Cape Division | Kimberley |

| Free State Division | Bloemfontein |

| Gauteng Division | Pretoria and Johannesburg |

| KwaZulu-Natal | Durban |

The tax court hears tax appeals. A tax court is presided over by a judge or an acting judge of the High Court, who is the president of the tax court. The judge is assisted by an accountant and a representative of the commercial community. In appeals relating to the business of mining or the valuation of assets, the representative must be a registered mining engineer; or a sworn appraiser. Three judges hear a dispute if a dispute exceeds R50 million; or SARS and the ‘appellant’ jointly apply to the Judge-President.

The Judge President of the Division of the High Court nominates and seconds a judge or an acting judge of the division to be the president of the tax court. A secondment applies for a period, or for the hearing of a particular case.

The President of the Republic appoints the panel of members of a tax court for a term of office of five years. A member is eligible for reappointment for a further period or periods as the President may think fit. The President of the Republic may terminate the appointment of a member at any time for misconduct, incapacity or incompetence. A member’s appointment lapses in the event that the tax court is abolished. A member of the tax court must perform his/her functions independently, impartially and without fear, favour or prejudice.

The Commissioner of the South African Revenue Services appoints the registrar of the tax court. The registrar and persons appointed in the office of the registrar are SARS employees.

When the tax court sits to hear an appeal, the proceedings are not public. The president of the tax court may in exceptional circumstances, on request of any person, allow that person or any other person to attend the sitting. In such a matter, the court considers any representations made by the ‘appellant’ and a senior SARS official who appears in support of the assessment or ‘decision’.

The tax court makes the following orders in appeals –

(a) Confirm an assessment or decision;

(b) Order an assessment or decision to be altered; or

(c) Refer an assessment back to SARS for further examination and assessment.

In the case of an appeal against an understatement penalty imposed by SARS, the court may reduce, confirm or increase the understatement.

Appeal against the decision of the tax court

The taxpayer or SARS may appeal against a decision of the tax court. An appeal against a decision of the tax court lies—

(a) to the full bench of the Provincial Division of the High Court which has jurisdiction in the area in which the tax court sitting is held; or

(b) to the Supreme Court of Appeal, without an intermediate appeal to the Provincial Division, if—

(i) the president of the tax court has granted leave under the rules; or

(ii) the appeal was heard by the tax court

Labour Courts and Labour Appeal Courts

The Labour Courts have the same status as a High Court. They adjudicate matters relating to labour disputes between an employer and employee.

It is mainly guided by the Labour Relations Act which deals with matters such as unfair labour practices. The Labour Appeal Court hears appeals against decisions in the Labour Court and this is the highest court for labour appeals.

Website: Labour Courts (judiciary.org.za)

Land Claims Court

The Land Claims Court specializes in dealing with disputes that arise out of laws that underpin South Africa’s land reform initiative. These are the Restitution of Land Rights Act, 1994, the Land Reform (Labour Tenants) Act, 1996 and the Extension of Security of Tenure Act, 1997.

The Land Claims Court has the same status as the High Courts. Any appeal against a decision of the Land Claims Court lies with the Supreme Court of Appeal, and if appropriate, to the Constitutional Court. The Land Claims Court can hold hearings in any part of the country, if it thinks this will make it more accessible and it can conduct its proceedings in an informal way if this is appropriate, although its main office is in Randburg.

Website: Land Claims Court (judiciary.org.za)

Land Court

The Land Court Act, 2023 (Act 06 of 2023) published in Government Gazette 49372, GoN 3744, 27 September 2023.

To provide for the establishment of a Land Court and appeals against decisions of the Land Court; to make provision for the administration and judicial functions of the Land Court; to provide for the jurisdiction of the Land Court and Magistrates’ Courts for certain land related matters; to provide for mediation procedures; to amend certain laws relating to the adjudication of land matters by other courts; and to provide for matters connected therewith.

Traditional Courts

The Traditional Courts Act, 2022 (Act No. 09 of 2022) published in Government Gazette 49373, GoN 3745, 27 September 2023.

To provide a uniform legislative framework for the structure and functioning of traditional courts, in line with constitutional imperatives and values; and to provide for matters connected therewith

Magistrates’ Courts

The Magistrates’ Courts are the district courts and the regional courts.

The district courts hear limited types of civil cases. They cannot deal with certain matters such as divorce, arguments about a person’s will and matters where it is asked if a person is mentally sane or not.

The types of civil matters that the magistrates’ courts hear are set out in the Magistrates Courts Act (32 of 1944 as amended). With effect from 27 March 2014, district courts hear matters up to the amount of R200 000. Regional courts hear civil matters above R200 000 up to and including 400 000. The Minister may change these amounts at any time by notice in the Gazette.

Some of the civil matters that the Magistrates Courts hear are:

(i) delivery or transfer of any property, movable or immovable;

(ii) ejectment against the occupier of any premises or land;

(iii) matters arising from a mortgage bond;

(iv) matters arising out of a credit agreement;

(v) other matters not already set out above, such as claims for damages caused negligently to a vehicle or injuries to a person.

Divorces

In addition to civil matters, a regional court hears:

(a) the nullity of a marriage or a civil union;

(b) divorces and ancillary matters; and

(c) matters in terms of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, 1998 (Act 120 of 1998). A regional court in these matters has the same jurisdiction as a High Court. The Regional Magistrate may be assisted by two assessors to advise on questions of fact.

Criminal matters in the Magistrates’ Courts

The State prosecutes people who are charged with breaking the law. The criminal cases are held in the criminal courts. Criminal Courts can be divided into two groups:

Regional Courts

A Regional Magistrate makes the decisions in a Regional Court, sometimes with the support of lay assessors.

The Regional Courts deal with serious cases such as murder, rape, armed robbery and serious assault. These courts do not hear treason cases. The Criminal Law (Sentencing) Amendment Act (38 of 2007) obliges the court to sentence a person to life imprisonment for offences such as murder or rape. The convicted person must prove “substantial compelling” circumstances in order for the court to impose a sentence less than life imprisonment. A Regional Court may impose a maximum fine of R600 000 and a maximum sentence of 15 years in common law offences (no statute or act of Parliament determines the sentence for the offence). A statute may prove for a maximum term of imprisonment in excess of 15 years for specific offences. An example is the Drugs and Drug Trafficking Act (140 of 1992). The maximum sentence of imprisonment for dealing in drugs is 25 years.

District Courts

The district courts try the less serious cases. They do not hear cases of murder, treason, rape, terrorism, or sabotage. The maximum term of imprisonment in common law crimes (crimes that are not specified by a statute / an act of Parliament) is 3 years. The maximum fine is R120 000. A statute may provide for a maximum term of imprisonment in excess of 3 years for specific offences that are heard in the district magistrates’ courts.

Specialised Magistrates Courts

There are a number of specialised courts located at the level of the Magistrates’ Courts that deal with certain types of matters. They are the children’s courts, commercial crime courts and sexual offences courts.

Specialised Commercial Crimes Courts (SCCCs)

The Specialised Commercial Crimes Courts operate at the level of the regional courts. These courts hear commercial crime and organised commercial crime matters. The first SCCU was established in 2009. They have grown in number over the years and are now found in all nine regional divisions. See the table below for the spread of SCCCs in each regional division as at 2022. A Regional Magistrate presides in the SCCC. Commercial and organised commercial crimes are investigated by the commercial branches of the South African Police Services. These cases are prosecuted by the Specialised Commercial Crimes Unit of the NPA.

| Regional Division | Place where the SCCCs sit to hear matters |

| Eastern Cape Regional Division: | East London, Mthatha, Port Elizabeth |

| Free State Regional Division: | Bloemfontein |

| Gauteng Regional Division: | Johannesburg, Palm Ridge, Pretoria, Pretoria North |

| KwaZulu-Natal Regional Division: | Durban, Pietermaritzburg |

| Limpopo Regional Division: | Giyane, Polokwane Central |

| Mpumalanga Regional Division: | Mbombela |

| Northern Cape Regional Division: | Kimberley |

| North West Regional Division: | Mmabatho |

| Western Cape Regional Division: | Cape Town at Bellville |

Small Claims Courts

Small Claims Courts are established for a magisterial district. The court hears civil matters that arose in the magisterial district in which the Small Claims Court is situated.

The maximum amount of a claim that may be brought is determined in a Notice in the Government Gazette. In 2019 the amount was determined as R20 000. Natural persons are allowed to bring claims in the Small Claims Courts whilst businesses, for example companies, close corporations, solely owned businesses and partnerships, are not permitted to do so. Claims may be brought against a business. A claim may not be brought against the State.

There is no Magistrate or Judge in the Small Claims Court. The presiding officer is a Commissioner who is usually a practicing advocate or an attorney. Commissioners are appointed by the Minister of Justice and Correctional Services. The Commissioners render their services without any remuneration. Legal representation is not permitted during the proceedings in the court. The proceedings in the court are different from a Magistrates’ Court or the High Court. The Commissioner asks each party questions to determine what transpired in the case.

Some types of matters that the Small Claims Courts do not hear are divorce, the validity or interpretation of a will, the mental status of a person, defamation, malicious prosecution, wrongful imprisonment and wrongful arrest.

You can contact your nearest Small Claims Court through your nearest Magistrate’s Court.

Website: www.justice.gov.za/scc/scc.htm

Equality Courts

Equality Courts have been established to help someone who believes that they have suffered unfair discrimination, hate speech or harassment. The Equality courts were extended to the Magistrates’ Courts primarily to bring access to justice to the marginalized and vulnerable citizens to assert their rights.

Anyone can take a case to the Equality Court, even if you are not directly involved in what happened. This means a complaint to the court can be made against someone or an organisation you believe have failed to respect the rights of another person.

Proceedings in the High Courts are costly for the majority of people, however in the equality courts, legal representation is not a prerequisite and there are no cost incurred when lodging a complaint, thus making it easy to access.

In terms of the Equality Act the South African Human Rights Commission and Commission on Gender Equality are mandated to assist complainants in taking their matters to the Equality Courts.

Website: www.justice.gov.za/EQCact/eqc_main.html

Maintenance Courts

A maintenance court is not a specialised court per se. A very high number of maintenance applications are heard in the maintenance courts. The court is located at each Magistrate’s Court. A Maintenance Officer is in charge of the maintenance matter. The Maintenance Officer assists with application for child maintenance. Maintenance is at the request of the biological or legal guardian of the child. The maintenance sum received by the guardian is for the upkeep of the child. A child’s upkeep is not limited to groceries but encompasses all the necessary needs of the child.

A maintenance defendant is someone who is legally obliged to maintain a child. Paternity is proved through DNA testing. The amount that is necessary for the maintenance of a child differs from one family to the next in line with their living standards. The amount that the defendant can afford is important. The say so of a defendant and claimant about their income and the needs of a child does not suffice. Each party has to provide proof of their earnings and expenses.

Once a matter is in the maintenance court, if the defendant agrees to pay maintenance and both the defendant and the guardian of the child agree on an amount of the maintenance, then the maintenance officer will request the Magistrate to make the offer an order of court. This removes the need for a drawn out trial and streamlines the court process. If no agreement on the amount is reached or the defendant refuses to make an offer acceptable to the guardian of the child, then the maintenance officer will request the Magistrate to conduct a trial. In such an instance the Magistrate will consider all the financial circumstances and make an order for maintenance.

Legal representation is allowed. The proceedings are recorded but conducted informally due to the nature of maintenance matters. The Magistrate can ask many questions. Our maintenance courts are there to ensure that those who have a duty to maintain minors are held accountable.

A person may be criminally charged for a deliberate failure to pay maintenance that arose from a court order. The court must first establish that there was a deliberate default. If, for example, the debtor was not earning an income because he/she was unemployed during a particular time when he/she was liable to pay maintenance, then it cannot be said that the failure to pay was deliberate. If a debtor is found guilty of failure to pay maintenance, the person has a criminal conviction. Apart from a criminal prosecution, the debtor’s property may be attached and sold by the Sherriff in civil proceedings. A maintenance debt has the same effect as a civil debt. A maintenance debt is enforceable. A debtor’s pension, annuity, gratuity, emoluments or debt owing to the maintenance debtor may also be attached.

Follow this link for more information on how to claim maintenance.

Sexual Offences Courts

In order to combat sexual violence, especially against women and children, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DOJ&CD) reintroduced the Sexual Offences Courts in the country with the aim to:

- Reduce secondary victimisation often suffered by the victims when they engage with the criminal justice system, particularly the court system;

- Reduce the turnaround time in the finalisation of these cases; and

- Improve the conviction rate in sexual offence cases;

As of April 2022, 116 regional courts were upgraded to Sexual Offences Courts. A sexual offences court is defined as a regional court that deals exclusively with cases of sexual offences.

Hybrid sexual offences court is defined as a regional court dedicated for the adjudication of sexual offences cases in any specified area. It is a court that is established to give priority to sexual offences cases, whilst permitted to deal with other cases.

Follow this link for more information on Sexual Offences Courts.

Children’s Courts

A Children’s Court is a special court which deals with issues affecting children. Every Magistrate’s Court in South Africa is a Children’s Court. The children’s court also takes care of children who are in need of care and protection and makes decisions about children who are abandoned, neglected or abused. Any person/ child may approach the clerk of the children’s court when he/ she believe that a child may be in need of care and protection. The Children’s Court can place a child in safe care or refer the child and/or the parent to services that they may require.

Children’s Court does not deal with criminal cases.

Follow this link for more information on the Children’s Courts and Child Justice issues.

___________________

Amended by the Chief Directorate: Policy Development, Branch: Court Services, 08 Aug 2022.

Referral 4

Gangs and youth – Insights from Cape Town

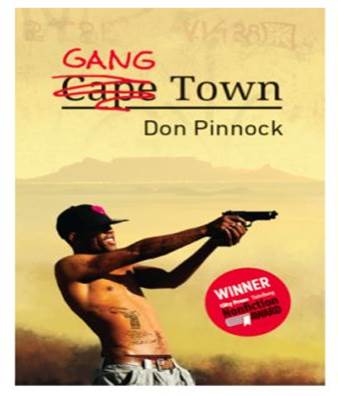

The content of the page is based on the book ‘Gang Town’ by Don Pinnock, which insightfully distils the knowledge of decades of research into gangs in Cape Town.

A special thank you to Don Pinnock for providing SaferSpaces with this introduction.

Related resources

01 Nov 2015 The Campbell Collaboration

A network of violence: Mapping a criminal gang network in Cape Town – Report/Study

28 Nov 2014 Institute for Security Studies

Content

- A tale of two cities

- What is a gang?

- Why are there gangs?

- Are there solutions?

- More information

Fixing the gang problem means solving the adolescent problem, says Don Pinnock in this introduction to gangs and youth. [Picture: Lindsay Mgbor/Department for International Development]

A tale of two cities

Cape Town is essentially two cities. One is beautiful beyond imagining on the slopes of Table Mountain, the other one of the most dangerous cities in the world where police need bullet-proof vests and sometimes army backup.

Here gangs of young men rule the night with heavy calibre handguns defending turf for drug lords, dispensing heroin, cocaine, crystal meth, cannabis and fear. In both a historian and a criminologist, I am interested in the crimes they do and the crimes done to them, why it is so and how it came to be like this.

In a single year ending in March 2015 more than seventeen thousand people were murdered in South Africa. This is higher than some countries at war. Around 600 000 other violent crimes were reported, including attempted murder, rape, robbery and assault.

The country’s murder rate per 100 000 is 34.3 per 100 000 (in 2016/17), one of the world’s highest. In Cape Town it’s much higher at 51.6 . This number masks the city’s huge internal disparities. In Nyanga, it’s estimated the murder rate is above 200 per 100 000. In 2012 contact crime in the Western Cape was 1 852 per 100 000. Much of this is attributed to gangs.

This is a brief overview of what is seen to be a gang problem in the city, followed by the underlying reasons and, finally, by a number of proposed solutions.

What is a gang?

Any formal or informal ongoing organisation, association, or group of three or more persons, which has as one of its activities the commission of one or more criminal offences, which has an identifiable name or identifying sign or symbol and whose members individually or collectively engage in or have engaged in a pattern of criminal gang activity.

This official definition from South Africa’s Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA) is so broad that it’s almost unworkable. Mostly the police simply ignore it unless there have been multiple convictions.

My definition of a criminal gang (there are other types of gangs) is, on the one hand, simpler, on the other more embracing:

A gang is a group of people with common interests who come together with common criminal purpose.

There are some general things we can say about such gangs:

- They’re an urban phenomenon found in most cities throughout the world where there’s crowding and low income.

- They’re mostly found within particular types or urban structure: tenements, low-cost neighbourhoods and squatter areas.

- They’re generally in areas of relative (not absolute) poverty

- They’re mainly a male youth phenomenon.

- They’ have to do with identity.

- There are often parental attachment issues.

- There can be connections to mental & physical health issues.

- There’s almost always a drug connection.

- There are very often education issues – high percentages of gang members have dropped out of school early.

- There are often, but not always, links to a criminal economy.

- They have a bad rap and use it

They can be structured as:

| Heirarchies, which are highly structured and bureaucratic with centralized control systems. | Networks, which tend to have fluid nodes and supply chains. These are harder to take down. | Markets, which buy and sell illicit products and services and are generaly fiercely territorial. | Clans, which are family-like and work through reciprosity and blood loyalty and display membership through ceremony, clothes and tattoos. |

For many young people, gang membership is a rite of passage into manhood and the urge for this type of associations is very old and embedded in many traditions.

It is a time of anticipation for something other – a longing for magical transformation and a rejection of the mundane. It demands ritual space, a time when a child needs to find the unknown man and woman inside themselves. It’s a time when we become obsessed by heroes, performance and ritual.

Why are there gangs?

Cape Town is an enigma. It’s one of most spectacular cities in the world and also one of the most violent. In 2015 there were over 2 000 murders – an average of six a day.

If the media is an indicator, this is a city drenched in gang violence. But are gangs at the heart of this violence? Police calculate that 11% of murders in the city are due to gang violence, the rest are domestic violence or the result of shebeen brawls.

But there are still a lot of gangs, and we need to explore why. One of my early discoveries was that Cape Town doesn’t have a gang problem so much as a youth problem of which gangs are one of the outcomes. Fixing the gang problem means solving the adolescent problem.

In 2016 nearly half (49%) of young people aged 15 – 35 were unemployed. In January 2017 South Africa had the highest recorded youth unemployment in the world. Half the kids who start school don’t make matric and 3.4-million aged 11–24 are not in education, employment or training. In Cape Town that figure, at last count, was 317 000.

Around five million young people are living in a household where nobody has a formal job and 26% are in child-headed households. The conclusion is that a huge majority of these young people are on the streets with nothing to do. And trouble follows idle hands.

Social disruption and family breakdowns

Central to the gang problem is opportunity difference and family breakdown. The old working class areas were socially integrated neighbourhoods with extended families which exerted high levels of social control.

Journalist Brian Barrow captured the sense of community this way:

Children everywhere. Shouting, laughing, whistling, teasing, darting between old men’s legs, running between fast-moving buses and cars and missing them by inches with perfect judgement. Poor, underfed children but cheeky, confident, happy and so emotionally secure in the bosom of their sordid surroundings. Everyone loved them. To them, it seemed, every adult on those busy streets was another mother, another father.

In the 1960s and 1970s Cape Town restructured along racial lines. All communities deemed non-white were ripped out and relocated to the Cape Flats. District Six is now grass and rubble where the social centre of the city used to be.

After 1994 Cape Town was recast as a world-class neoliberal city. This approach requires that the city is made safe and profitable for investment. Problems were largely pushed to the periphery and bad neighbourhoods remained bad neighbourhoods where poverty continued.

This was compounded by massive in-migration from rural areas – a nightmare for the city’s planners. In the past 22 years some things have got better for some but worse for many and many toxic environments remain.

What was the impact of these changes of on parents in these socially churned-up areas?

In search of role models

One of the biggest indicators for male delinquency is absent fathers. They may be absent emotionally, abusive or simply not there. Around 60% of births in the Western Cape are to single mothers. So, in the absence of role models, how do young men assert their masculinity?

The dominant masculinity in movies or on billboards are affluent, light-skinned or African heterosexual men and not achievable for most. Yet such masculinity is held in higher esteem in areas of major gang activity than elsewhere. Their hyper-masculinity swings between being the super-hero of a Hollywood blockbuster and a useless, socially despised ‘skollie’.

Respectability is out of reach, but they’re able to approach the desired values of toughness, success and control through crime. And gang bosses – with flashy cars, beautiful women and obvious power – are the role models.

It’s hard to be a young man in a low-income, high risk neighbourhood.

Mothers and epigenetics

Something else to consider is bio-social adaptation to environmental stress which begins even before a child is born. Its mother is IN an environment and IS an environment. Her nutrition, chemical intake or stress levels are signals that effect an embryo’s development.

Hyper stress or drug use by a mother can lead to an overdevelopment in the developing child of its dopamine system and an underdevelopment of its serotonin system.

Dopamine neurotransmitters are the ‘seeking’ system for things like exploring, foraging or sex. It prompts you to ‘go for it’. It raises levels of impulsive action, aggression and desire for reward. Gaining the goal is experienced as pleasure. The serotonin does the opposite – it cools you down, regulates emotion and behaviour, and inhibits aggression.

The effect of this altered balance kicks in, particularly, during puberty. There’s a direct relationship between dopamine highs and aggressive behaviour. Lower serotonin/higher dopamine means lowering of inhibition, increased impulsiveness, public spectacle hyper-masculinity and a greater predisposition to engage in violent behavior and lower overall resilience.

There is also a problem of early emotional attachment. Resilient youths seldom offend or resort to violence. Emotional resilience comes from loving attachments and safe surroundings.

Children growing up where that is absent have trouble making sustaining emotional connections. They have problems with their own feelings and the feelings of others. They carry feelings of shame and anger which they generally hide with bravado and, often, violence. They’re edgy and lock their emotions in a psychological vault. They are drawn to others like themselves without empathy, sympathy and caring.

These kids often turn to violence and aggression because they know these are a reliable method for reasserting their existence. Aggression gets them what they want. ‘I hurt others therefore I am.’

How about education?

In 2016 around 800 000 pupils sat down to write their final matric exams. That was about half of the number who had started school 12 years earlier. That means nearly a million young people failed to achieve the first rung of almost any career. A survey of grade six pupils across South Africa found that in 75% of schools, between about a quarter and half of the learners were functionally illiterate.

One third of young people in the Western Cape under 25 are not in education, employment or training. Most of them are on the streets with nothing much to do. These kids are essentially being socialized into failure.

Drugs

Cape Town is awash with drugs, from cocaine and heroin to chrystal meths and nyope, a low-grade heroin cut with anything from rat poison to chlorine.

Their clandestine, illicit, syndicate-driven use is destroying families, causing epigenetic problems in mothers, fatherlessness, raising levels of violence through turf wars, wasting police time chasing dealers and users, clogging courts and overfilling prisons.

The only sensible solution seems to be to follow the Portuguese example: decriminalize and institute systems of harm reduction.

Are there solutions?

The answer to the question is: of course there are. But we need to first ask what we mean by solving the gang problem? If we mean solving crime, that’s a big ask.

What I’m more interested in is to figure out how to solve violence and hopelessness among young people who, as things stand, have no alternative.

Helping young people live meaningful, resilient lives

Most members of gangs are young people – particularly young men who are seeking an identity; who have with little money yet need stuff in high-density urban areas; and who have time on their hands and plenty of adolescent edginess and energy.

The real question is not so much about gangs, but what can we do to help young people live meaningful, resilient lives in environments that favour development of gangs, crime and violence?

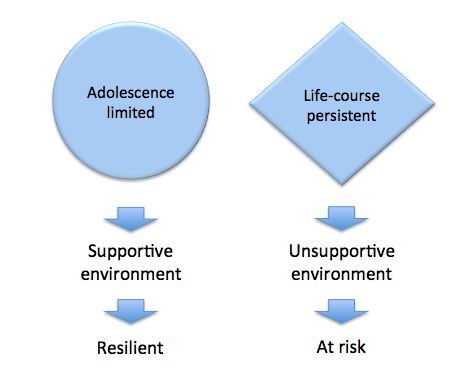

It is pertinent to ask: Which young people? All adolescents have the tendency to push the boundaries. While for many youthbad behaviour is limited to adolescence, there are others whose risky behaviour becomes life-course persistent due to epigenetic stress, attachment problems, fatherlessness and high-risk environments. It is these about whom we need concern ourselves.

Rethink Education

South Africa spends a huge amount on the roll-out of education but, for most kids, the education system is dysfunctional.

There tends to be a false dichotomy between hand and mind work, with craft skills less valued. Some people work best as mind workers, others as craft workers. It’s not a statement of intelligence but of aptitude.

If young people feel the skills they possess and interests they have are not valued, this might explain the high school dropout rate.

Rethink family & community

The first 1000 days from conception create the cognitive groundwork for the rest of a person’s life. A solid grounding at this stage has been proved to bring down violence and aggression levels 16 years later.

That’s why implementing the Early Childhood Development Policy is so important. Loving attachment is essential in forming resilient children. Resilience is what helps young people succeed in life and avoid gangs, drugs and early childbirth.

Rethink policing & prisons

Containing is what needs to happen when young people fall foul of the law.

The first stop is policing and it’s not doing too well. We need to know what policing can’t do. They cannot – and should not be expected to – solve the gang problem. Their job is to contain it until it’s solved by other departments..

Meanwhile this is how policing could be improved:

Re-educate police officers prone to violence or corruption.

- Improve the quality of new recruits and quality of training.

- Reintroduce professionalism and pride by employing only the best person for the job.

- Improve police management to curb corruption.

- Simplify grievance procedures so communities can report corrupt officers.

- Reinstate promotions based solely on merit.

- Establish an independent, specialised anti-corruption unit.

- Make the Independent Police Investigative Directorate truly independent.

Rethink prisons

South Africa’s prisons are failing for four reasons:

- They fail to change and often entrench criminal behaviour;

- They damage people who are already emotionally damaged;

- They ‘cook’ crime by housing large numbers of criminals together; and

- By not expunging an ex-prisoner’s record for many years, they stigmatise and make returning to crime the only option.

The solution is to transform prisons into schools of industry that turn out artisans and deal with the very real psychological problems of the people in their care.

If prisons are to be effective they must heal the damage done by society and provide skills

to reintegrate inmates back into it.

Reclaim the neighbourhood

The way neighbourhoods are structured has a direct influence on gang activity. Blocks of flats with poor street access favour gang activity because of poor community surveillance.

Any restructuring of neighbourhoods or rebuild plans need to incorporate space for extended families and have verandas for informal community surveillance (one of the reasons District Six worked as a community). We need to value and support grandparents: they are the anchors of any community.

Reduce the flow of illegal drugs

Around 120 000 young people in the Western Cape could be using some sort of illegal hard drug. What we have to do is reduce the harm they can cause – especially to young people. To do that, we need to understand why kids take drugs. One of the main causes of drug taking is sadness, a failure to fit in and the absence of loving relationships.

Source: Safer Spaces

Referral 5

13-year-old learner takes her own life after bullying

Written by Jonisayi Maromo – Journalist – iol.co.za

The Free State department of education said Mbali’s mother found a note detailing the reasons behind her daughter’s extreme decision.

Image by: Adrian de Kock / Independent Newspapers

A 13-year-old Grade 7 learner, Mbali Mlaba, tragically took her own life after reportedly being bullied at Vulindlela Primary School in Harrismith, located in the Thabo Mofutsanyane District of Free State.

Spokesperson for the provincial department of education, Howard Ndaba, said it is alleged that Mbali was repeatedly bullied by a classmate who accused her of cheating during a class test.

“According to reports, Mbali’s mother found a note detailing the reasons behind her daughter’s extreme decision,” said Ndaba.

“The learner had expressed fear of her classmate, who had assaulted and bullied her in the previous term, and had even requested to be transferred to another school.”

The Free State Department of Education emphasised that it takes all incidents of bullying seriously, and is committed to creating a safe and supportive learning environment for all learners.

“The department recognises the severe consequences of bullying on learners’ well-being and mental health. We are committed to providing support to learners and educators to prevent such incidents and promote a culture of kindness, empathy, and respect,” said Ndaba.

He said psycho-social support has already been provided to learners and educators affected by the incident.

“The department urges parents, learners, and the community to work together in creating a safe and supportive learning environment,” said Ndaba.

“If you or someone you know is struggling with bullying or any other issue, please reach out to us. We are committed to supporting you. Let’s work together to prevent bullying and ensure our schools are safe and supportive for all learners.”

Meanwhile, Free State MEC for Education, Dr Mantlhake Julia Maboya, has sent heartfelt condolences to Mbali’s.

“We are deeply saddened by the tragic loss of a Grade 7 learner from Vulindlela Primary School,” said Maboya. “We extend our heartfelt condolences to the family, friends, and loved ones of the deceased during this incredibly difficult time.”

‘She asked for transfer to another school: Shock as bullied learner dies by suicide

“Bullying” means any unwanted, aggressive behavior committed in person or by electronic communication directed toward another person or group that results in or is reasonably perceived as being done with the intent to cause physical harm or negative situations for the targeted individual or group, and is communicated in such a way as to disrupt or interfere with the person or group’s peaceful living, and that is repeated or is highly likely to be repeated.

Bullying is intimidating another person and it causes psychological harm to the victim. Bullying is a criminal activity and should be punished as such. – Zenzeleni Progressive Movement

Zenzeleni Action Plan

Setup anti-bullying report lifeline with trained staff to help report the matter immediately to authorities.

Corporal punishment to perpetrators.

Referral 6

Mother Assaulted By Teenage Daughter

Despite having protection order, 73-year-old mom assaulted by her son, in her home

Written by Jonisayi Maromo – Journalist – iol.co.za

A 73-year-old woman was assaulted by her son, in her house at Matolong village, in Taung. File Picture

Published May 5, 2024

A 41-year-old man is scheduled to appear before the Taung Magistrate’s Court on Monday after he allegedly contravened a protection order issued under the Domestic Violence Act.

Despite the existence of the protection order, the 41-year-old man allegedly assaulted his 73-year-old mother in her house, according to North West provincial police spokesperson, Colonel Adéle Myburgh.

“It is alleged that on Thursday evening, May 2 2024, the accused came home and assaulted his 73-year-old mother in her house at Matolong village, in Taung. The incident occurred after a protection order was earlier granted against her 41-year-old son,” said Myburgh. The son was arrested on Friday, shortly after the incident was reported to the police. “The suspect will be appearing before the Taung Magistrate’s Court on Monday, May 6 2024,” said Myburgh.

‘Boy was disrespectful’: Grandfather, 87, sentenced for shooting 13-year-old grandson

Written by Jonisayi Maromo – Journalist – iol.co.za

An 87-year-old man was sentenced to five years in jail after he shot and injured his grandson. File Picture

Published Mar 11, 2024

The Mhala Regional Court in Mpumalanga sentenced an 87-year-old man to five years imprisonment after he was convicted on charges of attempted murder.

The name of the convicted and sentenced octogenarian is withheld to protect the minor involved.

The Mpumalanga court heard that in August last year, the mother of the 13-year-old boy was at work when she received a call informing that her son had been attacked.

The teenager had been attacked by his grandfather, at Marite Trust near Hazyview.

“Upon arrival, she (the mother of the teenager) learned that her father had shot her son on his lower back. The child was taken to a nearby hospital,” said Mpumalanga provincial police spokesperson, Colonel Donald Mdhluli.

The grandfather informed the child’s mother that her son “was very disrespectful hence he shot him”.

When police arrived at the scene, they immediately arrested the 87-year-old man, and the police also found about 87 live ammunition in the house.

“The suspect was brought to court and went on trial. He then got convicted, hence he was sentenced to five years imprisonment. The court also declared him unfit to possess a firearm,” said Mdhluli. Meanwhile, provincial commissioner of police in Mpumalanga, Lieutenant General Semakaleng Daphney Manamela has commended the investigation team, the prosecutors, and the judiciary for the collaboration which resulted in the sentencing of the grandfather.

“We hope that the sentence will serve as a deterrence to perpetrators of crime against the minors,” she said.

Boy, 16, abused mum for eight months, fracturing her rib and threatening to kill her with chopper

Christine Tan – UPDATED Nov 21, 2024, Straits Time

SINGAPORE – A mother silently endured abuse by her 16-year-old son for at least eight months, suffering injuries that include a fractured rib.

Her husband witnessed the attacks, which took place between March and November 2022, but did not intervene.

On one occasion, the slim-built boy pulled his mother, who is about his height, into the kitchen and threatened her with a chopper, telling her “I will kill you”, court documents showed.

His brother, who was 18 then, told him he would get in trouble and advised him to put the chopper aside. He complied before the police arrived at their home, where the boy lived with his parents and brother.

The teen on Monday pleaded guilty to two counts of voluntarily causing hurt, one count of voluntarily causing grievous hurt, and another charge of criminal intimidation.

Another two charges of voluntarily causing hurt were taken into consideration for sentencing.

There is a gag order on the identities of the accused and the victim due to the boy’s age.

Deputy Public Prosecutor Kwang Jia Min said the teen had a history of hitting his mother, who was 52 years old then.

The boy, who has had anger management issues since 2019, physically assaulted her every two to three weeks. Concerned for his well-being, his parents had him referred to a family service centre for counselling. He also received help at the Institute of Mental Health, where he was assessed to have anxiety issues.

The offences were committed after he stopped attending the counselling sessions in December 2021.

In March 2022, the accused punched his mother in the face several times, bruising her jaw.

He hit her again two months later, this time causing her left cheek to swell and bruise.

On Oct 17, the teen stayed up to study for his O-level examinations until about 5am the following day.

He got up at 10am, and was angry at his mother for not waking him up earlier as he had an English exam that day. He then punched her several times.

Following the incident, the victim arranged for her son to meet his counsellor on Nov 4.

She set alarms at 15-minute intervals to wake him up on time for the session. But he smashed the alarm clock instead.

The victim ended up attending the counselling session by herself. When she returned home later that day, he accused her of not waking him up for the appointment.

He was undergoing a guidance programme at the time, and missing a counselling session meant the programme would be extended.

The boy flew into a rage and rained blows on his mother, hitting her in the ribcage area, face and head.

Her ribcage ached after the assault, and she had a cut on a lip. A medical report later revealed that she had a fracture on a left rib.

But the victim did not report her son’s actions to the police.

A few weeks later, the two of them were in his bedroom discussing which school he should enrol in after his O levels when he flew into a rage because his mother could not answer some of his questions about the school’s curriculum.

He hit his mother on the head with a hardcover report book. She ran into her bedroom, locked herself inside and called the police.

But her son found the key to the bedroom, opened the door and pulled her into the kitchen, threatening her with a chopper.

Mom tells court son assaulted her despite protection order

By Guy Rogers – 30 November 2024 – The Herald

In the midst of 16 Days of Activism for No Violence Against Women and Children, a Motherwell woman described in court on Friday how her son punched her, pushed her to the ground and called her a witch.

Phumza Rhamnculana, 67, burst into tears as she told the Motherwell magistrate’s court that her son, Siyabulela Rhamnculana, 31, had already breached one protection order she had against him…

Parental Abuse: What to Do When Your Child or Teen Hits You

By Kim Abraham, LMSW and Marney Studaker-Cordner, LMSW – Empowering Parents

If you are the target of parental abuse, you’re probably living in fear every day of what your teen will do next, always waiting for what will set off a volcanic eruption.

Parental abuse occurs when a child — usually a teenager but sometimes a pre-teen — engages in behavior that is abusive toward a parent. It may be a one-time incident or it may escalate in frequency, even to the point of a daily occurrence. It can range from verbal abuse (for example, swearing at or threatening a parent) to intimidation to outright physical assault. And although parental abuse is often associated with explosive anger and rage, the abusive behavior may occur with no emotion: a quiet, deliberate act of harm used by a teen to maintain power over a parent.

Living in Fear

Parental abuse can leave a person feeling embarrassed, ashamed, angry, terrified, and unsure of what to do. These are feelings that we call “parent paralyzers,” feelings so intense that they overtake logic and reason and leave us questioning ourselves and trapped in uncertainty about what direction to take.

If you’re in this situation with your child, know that you are not alone and that you are not different in some way. We see abuse happen in every type of family—it doesn’t matter how much money you make or your background. This type of abuse could happen in any family.

Jennifer’s Story

Jennifer’s son began hitting her when he was 14 years old. “I just didn’t know what to do,” she told us. “If anyone else had hit me, I would have called the police. But this was my son!”

“I didn’t want him arrested but I wanted the abuse to stop. I was ashamed to admit to my family what was going on and I knew they would take action, even if I didn’t. The situation was intolerable but I couldn’t take action. I felt trapped, as if I was in a car without brakes.”

Is My Child’s Behavior Abusive?

If your child or teen is harming you physically, you are being abused. It’s that plain and simple.

One man raising his granddaughter admitted, “I knew her behavior was unacceptable; she would throw things whenever she got mad and one time she hit me in the chest with an ashtray. After that, she started throwing things with the intention of hitting me. I just never thought of it as abusive.”

No one wants to believe their child could be abusive. Emotion can “muddy the waters,” make us question whether or not things are as “bad” as our gut tells us they are.

Ask yourself: if your child was anyone else — a neighbor, a co-worker — would you consider his or her actions to be assault or abusive? This will help you take the emotion out of evaluating a situation.

Warning Signs of Parental Abuse

Sometimes a situation escalates without us even realizing it. The following are some potential warning signs that a child’s behavior is bordering on abusive:

1. Feeling Intimidated

It’s normal to feel your child is pushing boundaries to get what he wants. Kids will ask over and over for something they want, until a parent can finally snap, “I told you no!”

What’s not typical is to feel that if you don’t give your child what she wants, she will retaliate in a way that is harmful to you. Intimidation is a way of frightening someone else into doing something. It may be the words, the tone of voice, or even just a look.

2. Extreme Defiance

Yes, kids can be defiant, even your typical child. But when it reaches a point that your child has no respect for your authority as a parent, outright defying the rules of your home with no fear or concern of consequences, it’s a potential sign of escalation. Many kids can be defiant without violence; however, extreme oppositional behavior can be part of a more serious picture.

3. An Escalating Pattern of Violence

Kids get angry, slam doors, throw things in a fit on the floor in their room. You can probably remember a time when you were growing up that you got mad and smashed something. But you learned that this behavior didn’t get you what you wanted and – in fact – may result in you having to re-buy things you valued.

But when a child or teen’s behavior continues to escalate to the point of destroying property, punching walls, shoving, hitting things near you, throwing things that “almost” hit you, making verbal threats, or violating your personal boundaries (“getting in your space”), this is a pattern that may indicate abusive behavior.

Why Is My Teen Abusive?

When a child or teen turns abusive, it’s natural to ask “Why?” Many parents feel guilty, blaming themselves for their teen’s behavior: “If I was a better parent, my child wouldn’t be acting this way.”

The truth is, there can be several underlying factors contributing to parental abuse including poor boundaries, substance abuse (by either a parent or child), poor coping skills, underlying psychological conditions (such as ADHD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder) and learned behavior. Some kids behave violently due to poor coping skills. Others are more deliberate and enjoy the power that comes from intimidating a parent.

Remember: we can try to understand what’s going on in any situation, but there is no excuse or rationale for abusive behavior.

Responding to Parental Abuse

Aggressive and abusive behavior is not a part of typical childhood or adolescence. It’s not a stage that your teen will “grow out of” if you ignore it. If you’re dealing with parental abuse in your home, your child is violating the rights of others. It doesn’t matter that it’s his parent’s rights; that doesn’t make it any less serious or illegal. Your home is the place where your child will learn how to interact in the world. He is learning what’s acceptable — and what’s not. He’s learning about consequences for behavior and accountability.

One of the hardest tasks a parent can be faced with is responding to their own child’s aggression or abuse. It’s natural to feel torn. On one hand, it’s instinctual to protect your child. On the other hand, nothing can push a parent’s buttons of anger, disappointment, and hurt like a child’s abusive behavior. Some days you may feel emotionally stronger than others. Only you can decide what you’re able to follow through with at any given time. Here are some suggestions:

1. Clearly Communicate Boundaries

Make sure your child understands your physical and emotional boundaries. You may need to clearly state: “It’s not okay to yell or push or hit me.”

If you’ve said this to your child in the past, but allowed her to cross those boundaries in the past without consequence, she’s gotten mixed messages. Your words have told her one set of boundaries but your actions (by accepting being yelled at or hit) have communicated another set of boundaries.

Make sure your non-verbal communication (what you do) matches your verbal communication (what you say).

2. Clearly Communicate Consequences For Abusive Behavior

Tell your teen:

“If you hit me, throw something at me, or otherwise hurt me physically, that’s called domestic violence and assault. Even though I love you, I will call the police and you will be held accountable for your behavior.”

Then – again – make sure your actions match your words. If you don’t think you can follow through with contacting the police – don’t say you will. This will only reinforce to your child that you make “threats” that won’t be carried out.

You may choose to provide other consequences, other than legal, that you enforce. If a friend physically assaulted you, would you let her borrow your car or give her spending money the next day? Probably not.

3. Contact the Authorities

We don’t say this lightly or without understanding how difficult this can be for a parent. Some parents are outraged at a teen’s abusive behavior and react: “I’ve got no problem calling the cops on my kid if he ever raises a hand to me!” Other parents struggle, worrying about the long term consequences of contacting the police or unable to handle the thought of their child facing charges.

Remember, if your teen is behaving violently toward you now, there is the risk that this will generalize to his future relationships with a spouse, his own children, or other members of society. You are not doing him a favor by allowing him to engage in this behavior without consequence.

Related content: When to Call the Police on Your Child

4. Get Support

Parental abuse is a form of domestic violence. It’s a serious issue and needs immediate attention and intervention. Domestic violence has traditionally been characterized by silence. As hard as it is, break that silence. Get support from family or friends – anyone you think will be supportive.

If your natural supports tend to judge you and you’re afraid it will only make the situation worse, contact a local domestic violence hotline, counselor, or support group. For support and resources in your community, you can also call 2-1-1 or visit 211.org, a free and confidential service through the United Way.

The road to a healthier relationship with your child will very likely take time. There’s no shortcut or quick fix. It starts with an acknowledgment of the issue and accountability. If you’re facing this issue in your family, we wish you strength and empowerment.

Son brutally assaults his mother in Mumbai and his wife records the video.

A 13-year-old boy has been charged after police said he assaulted a mother and her son on a New Jersey street. The incident happened on June 19 on Lexington Avenue in Passaic, New Jersey. Beronica .

Source: abc6onyourside – mom-attacked-by-13-year-old-boy-who-told-her-son-to-go-back-to-mexico

Father assaults two-year-old, dumps her in tank – Tamil Nadu

KARUR: A two-year-old girl is battling for life after her 30-year-old father allegedly sexually assaulted her and dumped her in a water tank. The man has been arrested under the Pocso Act.

A senior medical officer at the government medical college hospital in Karur said the girl is currently undergoing treatment in a critical condition. The horrific crime happened during the early hours of Thursday. The girl’s parents worked at a brick kiln in their village in Karur district. The couple has a four-year-old son also.

The police complaint of the girl’s mother states the toddler went missing while she was asleep with her husband and son. She searched for her all over the home and went to the terrace where she found her skirt. Subsequently, she checked the water tank where the minor was floating unconsciously. The accused accompanied her wife during the search.

The girl was rushed to the government medical college hospital in Karur, where doctors concluded he was sexually assaulted. On Thursday, the Child Welfare Committee alerted the Karur all-woman police who, in turn, arrested the accused, police said.

Police sources say the man confessed during questioning that he took his daughter to the terrace while others were asleep. As she cried during the assault bid, he dumped her into the water tank and came back to the room and laid down as if nothing had happened. Source: New Indian Express – Tamil Nadu – Father assaults two-year-old, dumps her in tank

Referral 7

Class 8 student beaten up, sexually assaulted. The victim’s mother alleged the school did not help her pinpoint the perpetrators and refused to share CCTV footage with her

Amid an ongoing investigation into an alleged assault involving a 13-year-old victim at Stepping Stones Learning Center in Palm Springs, the child’s mother decided to take action of her own as she felt the situation was so dire. Source: Desert Sun – mother-son-who-allegedly-assaulted-palm -springs-learning-center-wants-justice

Referral 8

Each room told a gruesome story’: Mom shares letter to Sizzlers Massacre killer as family petitions for law change.

The family of Robert Visser has pleaded with President Cyril Ramaphosa and justice minister Ronald Lamola to consider changing laws that allow violent offenders to qualify for parole after just over 12 years in prison. 17 March 2021 – Aron Hyman Reporter

Eighteen years ago, Marlene Visser silently walked through a home in Cape Town, taking in the devastation. It was in this house that her son, Robert Visser, was brutally killed. In 2003, Woest and Trevor Theys tied up, shot, and slit the throats of nine men — Aubrey Otgaar, Sergio de Castro, Marius Meyer, Travis Reade, Timothy Boyd, Stephanus Fouche, Johan Meyer, Robert Visser, and Gregory Berghau — at Sizzlers, a gay massage parlour in Sea Point.

One man, Quinton Taylor, survived.